A recent post (see here) brought you the first part of an examination conducted by our Zooniverse Moderators R. Roberts (@GROBSTER) and Robert Croke (@SandyCycler) into documents relating to the U.S. sailors who were present at the momentous events at Fort Pickens, Florida during the early days of the rising crisis in the United States in 1861. In Part 2 of this special Community Discovery Series offering we take a “deep dive” into the correspondence of one of these sailors, one of the small number to have preserved wartime letters contained within an associated pension file. The letters were uncovered by R. Roberts while following up historical leads related to the Fort Pickens men. We have decided to transcribe the letters in full here, sharing with readers the first-hand words of a newly-wed couple who were attempting to navigate the Civil War on the Waters.

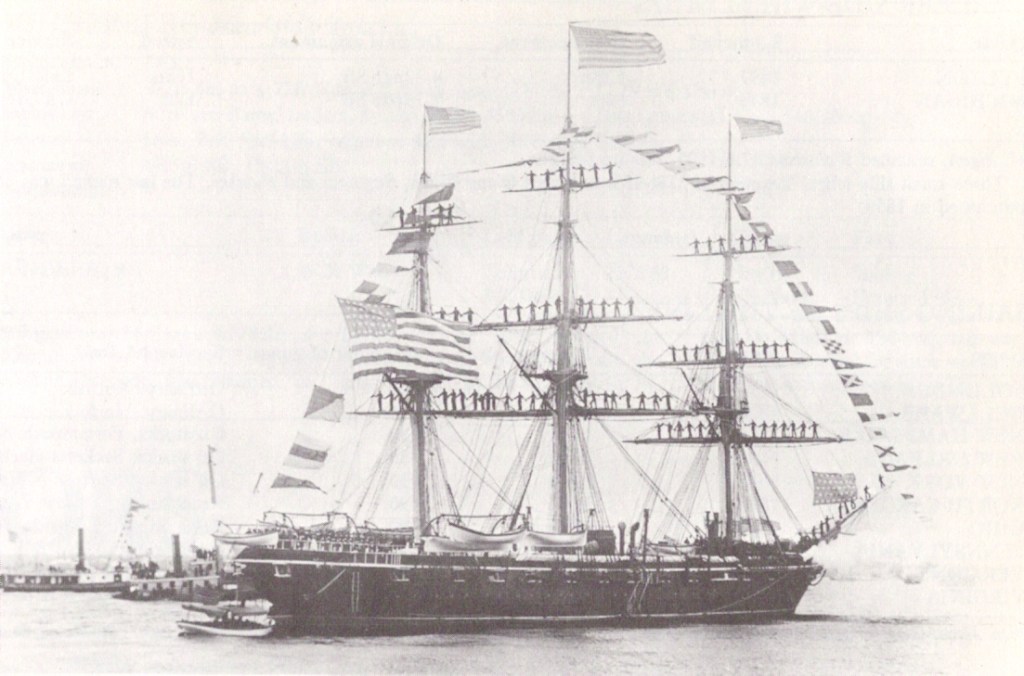

The Fort Pickens sailor whose words have come to us was named William Ashworth. Research by R. Roberts established that William’s birthplace was recorded as Manchester in England, and that he was 21-years-old in 1861. In that year he was described as 5 feet 5 inches tall, with blue eyes, brown hair and a fair complexion. A professional mariner, William decided to stay on with the United States Navy following his Fort Pickens adventure. He rejoined the service at Philadelphia on 14th November 1861, when the USS Brooklyn returned North following her cruise. Because of his maritime experience, the English immigrant was rated as an Ordinary Seaman. He would go on to spend most of the conflict in naval uniform, much of it aboard the vessels USS Brooklyn and USS Vicksburg. He was still serving even after the guns stopped firing; December 1865 found him aboard the USS Vicksburg in New York. The English career sailor survived his time at war, ultimately passing away in February 1890.

The reason some of William’s wartime letters survive is because his widow Mary Ann (known as Polly) submitted them after his death, in support of her own pension claim. Polly had kept them for thirty years. At the time (August 1892), she revealed that during the war “he [William] brought all of my letters and I kept all of his.” The couple had married in the midst of the conflict, tying the knot in New York City on 22nd November 1863. They afterwards spent their home lives in Brooklyn, when William was not “following the sea.” Polly felt compelled to submit the letters to the Federal Pension Bureau because she was struggling to otherwise prove her relationship to the wartime sailor. This was due to the fact that, although known as “William Ashworth” at sea, that was not the English sailor’s official name. The man Polly had married was called “William Nuttall.” In her testimony, Polly explained that while William had gone by the name Nuttall on land, he had chosen Ashworth for his maritime career. She later revealed William’s reasoning: “when he was eleven years old he ran away from home and to avoid being found by his father he assumed his mother’s name of Ashworth and went to sea.” The use of an alias was extremely common during the Civil War era, particularly among naval recruits. When selecting their “other” name, men most frequently opted for their mother’s maiden name, just as William had done.

Thus armed with the surnames of both William’s parents, we were able to explore English records for possible matches. One quickly emerged. Our research indicates that the home the young boy who had run away to sea was not the City of Manchester itself, but about twenty miles away. It was a place called Haslingden Grane in the West Pennines of Lancashire (for more on this “lost village” of Haslingden Grane, see here). Specifically, we think William may have grown up near a farm called “Doles Grane,”* the child of weaver William Nuttall and Betty Ashworth. William was baptized from there in January 1840.

And so to the letters. The earliest in the series dates to late 1863, and was written by William to Polly from the decks of the recently commissioned gunboat USS Vicksburg in New York. The couple had been married for a little over three weeks.

USS Vicksburg, New York, 17 December 1863

Dear Polly,

I now write to you for I do not expect to come ashore again before I come back but at any rate I will try on Saturday or Sunday. In this I send you the sum of 108 dollars because it is all I can get at present or I would send you more but I expect to send you more very soon or at least as soon as I can. Our Paymaster will not trust me with the money but he will mail it himself so as soon as you receive it and let me know if Tom has got work yet which I hope he has and doing well and tell him that I hope he has given up all idea of going to sea again. Also give my respects to Mr and Mrs Cain and should you go to W Mitchells give him and his wife my respects. If I should come ashore again I will gratify Robert what he wants as your fathers letter told me. I got it this morning. I must conclude by wishing you well from your affectionate husband,

William Nuttall.

You will please to answer this as soon as you received this and direct to William Ashworth, USS Vicksburg, Navy Yard, New York.

As was the case with many wartime letters, communicating details of the money being sent home was of paramount importance. It is interesting here that William notes his Paymaster would “not trust” the sailor with his own earnings. This was likely due to the fact that the Vicksburg was then in port at a major city, a circumstance that offered many temptations to a wartime sailor. Apparently, the Paymaster was seeking to ensure that the crew’s money would get to safely their families before it could be squandered away onshore. In another common sentiment found in Civil War Correspondence, and despite his own long years at sea, William expressed his desire that his relation Tom would find alternative employment rather than going back into naval service himself. Servicemen were often eager to see those closest to them avoid the harsh realities of military life. William’s next letter to his wife was written just three-days later. Where in his first letter he had referred to his wife as Polly, this time he addressed her by her given name, Mary:

USS Vicksburg, New York, 20 December 1863

Dear Mary,

I am very sorry to tell you that tomorrow we proceed to sea. I believe to Bermuda. I was in hopes to spend my Christmas in your company but as you say its perhaps all for the best. I am very sorry indeed that we are going so soon. Until this small affair is settled with the Cain family. Anyhow I will do my best [to] keep up a good heart. I will make it all right as soon as I possibly can to your satisfaction.

I must now close by wishing you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Give my respects to your father and Robert also my love to Sarah and Willie. We will be happy yet is the worst wish of your affectionate husband,

William Nuttall.

As William prepared for sea, his letter conveyed his disappointment at not being able to spend Christmas with his new bride, and his worry about personal matters with the Cain family. Although he suspected the Vicksburg was bound for Bermuda and operations against Confederate blockade runners, that was not to be the case. On 7th December a panic had been caused along the coast when a small group of Confederate sympathizers seized the steamer Chesapeake off Cape Cod, Massachusetts and diverted it to New Brunswick, Canada (for more, see here). In response, the Vicksburg was ordered off Sandy Hook, New Jersey to inspect commercial shipping and avoid a repeat of the incident. It was February 1864 before she steamed for her more permanent assignment, hunting blockade runners as part of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. William’s next letter came during this period, written from the waters off North Carolina:

United States Gunboat Vicksburg, Beaufort, North Carolina, 5 May 1864

My Dear Wife,

I yesterday received your letter and I was very glad to get it for I thought my letter had been miscarried and ten dollars $10 although it is not much it is too much for you to lose. We have been to sea for the last few days cruising. The first day out we caught a schooner (Indian) and sent her a prize to Washington. A friend of mine went in her so I sent a bit of a note to Robert with that double photograph with him with orders to give them to him or if he cannot go to forward them. I have not heard from Robert since I left New York. We are going cruising again to try our luck for a month. I am very glad to hear that Charlotte is going to set up herself in life and tell her I wish her much happiness also her husband although I have not the pleasure of being acquainted with him. You will also give my respects to Mrs and Mr Mitchell and tell John that I think he is real mean for not writing to me but perhaps he has not received my letters. I am sorry to hear of the disturbance between Tom Cain and his wife but I never expected they would hang out as long as they did. That was a very sad affray about the Chenango I lost a shipmate (John White) a Engineer as fine as man as ever I was with peace to his ashes. I must not forget to tell you that I now hold the most honorable position in the ship Signal Quartermaster but I get no more pay.

Tell your father that before two months I will get an appointment as an officer in the Navy and if it is approved I will be home about that time. You will give my love to all at home and my respects to all those who may think proper to inquire after your affectionate husband,

William Nuttall.

You will direct to and in this manner until further orders

Mr William

NuttallAshworth, US Steamer Vicksburg, BeaufortIn this I will send you 20 dollars for the mails have stopped so I do not know when I can write again.

This letter was the most important in the series for Polly with respect to her pension claim. While the earlier letters established her relationship, in this letter William had first signed himself “Nuttall” before crossing it out and writing “Ashworth,” conclusively proving for the Pension Bureau that he was one and the same man. As was usual for wartime correspondence, much of the content was taken up with concerns and news of home; people not writing enough, new marriages, a relationship seemingly on the rocks. In his professional life, it is apparent things were going well for William. The capture of the British blockade runner Indian was one of a number of successes the Gettysburg enjoyed during the war, and it guaranteed William a share of the resultant prize money. In addition, he had risen to the Petty Officer rating of Signal Quartermaster. While officially this meant he had special responsibility for signalling and signalling equipment, at this period it also entailed many of the duties of Chief Quartermaster (for more on these ratings, see here). Traces of the responsibility and standing William enjoyed aboard the Gettysburg can be seen in the language he used to let his wife know where to direct future letters, as he adopted an officious and very naval tone in instructing her to send them “to and in this manner until further orders.” It is evident that William had hopes to advance still further, with aspirations to eventually become a naval officer, something he clearly hoped would impress Polly’s father. The letter is also tinged with sadness over the loss of a former comrade. In April 1864 William’s friend John White had been aboard the side-wheel steamer USS Chenango as she embarked on her maiden cruise from New York to join the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Shortly after departure a catastrophic boiler explosion ripped through the vessel, scalding 28 men to death, including John.

The letter written off North Carolina was the final example from William Ashworth Nuttall preserved in the pension file. However, there was another wartime letter, of a type that is exceptionally rare among surviving pensions correspondence— a letter from Polly to her husband. She wrote it from New York in the summer of 1864:

New York, 12 June 1864

Dear Husband,

It is with pleasure that I write these lines to you hoping this will find you in good health as it leaves me at present. I received your kind letter dated May the 5th with 20 dollars in it and one dated April the 6th with 10 dollars in it and I wrote to both letters. Tom Cain wrote the answered letter. Mrs Donley was over the same day and she married to a man named Charles More and Mr Mathews is married to a young girl. I was to Mitchels and Tom Mitchels father fell down the stairs and broke his shoulder he was very bad when I seen him. Tom and his wife sends their best respects to you. I received a letter from brother Robert and he told me that he received the likeness. Father and Sarah and Willie sends their best respects to you.

I received no letter from your father as yet which is all as yet. From your affectionate wife,

Mary Ann Nuttall.

Polly’s letter is written in a matter-of-fact and formal style (down to signing off as “Mary Ann Nuttall”) that was extremely common among those with limited writing skills. Significantly, it reveals that Polly herself could not write— the letter was written for her by Tom Cain. This demonstrates the difficulties that the couple would have had in maintaining their correspondence during the war, and the reliance Polly had to place on others to communicate her messages to her husband on her behalf. The primary function of the letter was to inform William that the money he had sent had arrived safely, always a concern for servicemen far from home. But Polly and Tim also communicated a lot of other familial and local information in these few short lines, which shed light on the day-to-day lives and concerns of people in 1864 New York; the latest news re marriages, the ever-present risk of severe or debilitating injury, word of who had and who had not been heard from.

The final part of this special Discovery Series sequence will be available in the near future on the site, sharing some of R. Roberts work on the other men recorded in the Fort Pickens list. Among other things, it will demonstrate the significance and importance of the sequence of letters between William and Polly during this period. We close this post with a letter written on Polly’s behalf by Augustin J. Delap in June 1894. It offers a sorrowful insight into the struggles of working-class life for nineteenth century New Yorkers, and the sad struggles that Polly and her family endured in the years following William’s death.

212 Prospect St., Brooklyn, New York, 6 June 1894.

Dear Sir,

I write to you on behalf of Mary A. Nuttall widow of William Ashworth Nuttall alias William Ashworth, Seaman U.S.S. Brooklyn. This poor woman has a crippled boy who has spinal disease and has to be carried around all the time take all the time of mother, two daughters all the time to attend to him and leaves those poor people in terrible poor circumstances. In fact they have to live in miserable quarters and are not able to pay the few dollars a month they cost and have to move or be put out of course one daughter who is able to earn a little once in a while but not enough to pay rent so of course you know yourself that 8 dollars a month for widow and two for the boy is not enough to keep these 4 poor people and I think as I hope you will also that it is too bad for a U.S. Seaman and particularly one that helped to do as much good service as the U.S.S. Brooklyn and served 4 years in the U.S. service his family should have at least enough to live in.

Now what I want to beg of if it lays in your power to increase this poor widows pension if there is any possibility of doing so. Those lawyers has been charging this poor widow so much for doing the smallest work that she asked me as a friend of her dead husband to ask you for God Sake to increase her pension no matter how small it will to pay the rent at least.

Hoping that this petition will meet with a favourable reply with the prayers of this poor widow and unfortunate children.

I remain yours respectfully, Augustin J. Delap, 212 Propsect St., Brooklyn, New York.

In 1896, a $2 pension supplement was approved and backdated to help Polly care for her disabled son, whose name was David.

- Special thanks to Kilrossanty Remembers (@KilrossantyR) and Anne (@Annie_Beez) over on X for help with deciphering the placename on William’s baptismal record.

If you are interested in participating in the Civil War Bluejackets Project, you can head over to our Zooniverse Project Page to take part. We are always interesting in hearing what our community uncovers, so please let us know on Zooniverse Talk what you come across!