Recently Civil War Bluejackets and the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society have been collaborating as part of our efforts to identify African American sailors on the muster sheets. A number of Society members have joined our Zooniverse community, where they are making invaluable contributions towards uncovering the stories of these men. One of them, @Grobster, has been highlighting a number of interesting discoveries over on our Zooniverse Community Talk forum. @Grobster has been making particular note of some of the youthful African American boys in the muster sheets, even finding one- Richard Johnson of USS Aries– who was just 8-years-old. But in this post we are going to concentrate on another of the youngsters @Grobster has discovered- 3rd Class Boy Frank Branch, a boy of 12-years when he enlisted in the Union Navy. We have dived into the records Frank left behind, which provide us with an invaluable window into his life both in enslavement and in the decades after the war. What’s more, they even contain rare description of some of the tasks African Americans like Frank were asked to fulfill in the service- given to us in Frank’s own words.

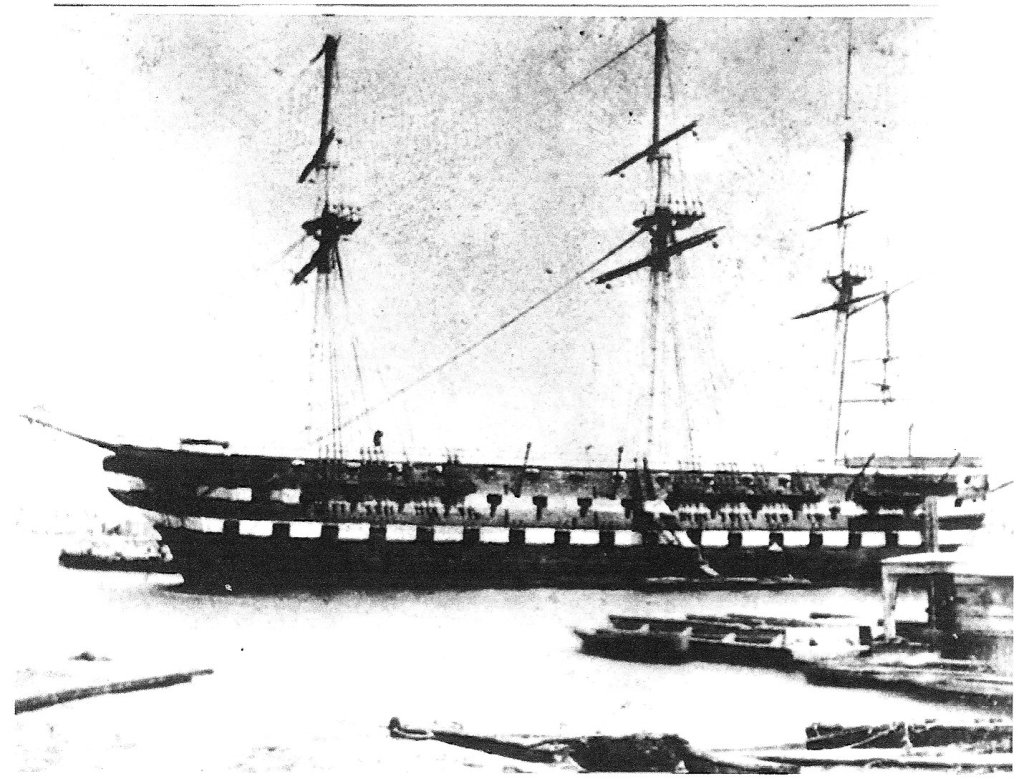

Frank Branch’s name first appears in the historical record in June 1862, when as a 12-year-old, 4 foot 6 1/2 inch boy he entered the United States Navy at Hampton Roads, Virginia. Assigned the lowest rating of 3rd Class Boy, the Virginia native joined the crew of USS Brandywine, a storeship and supply vessel tasked with servicing the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Even by naval standards, work on these ships was particularly arduous, given the almost constant manual labour required in the loading, unloading and transfer of equipment and supplies. Just as with the Army, the Navy disproportionately assigned African American men to such monotonous and onerous roles, as they were among the least desirable in the service.

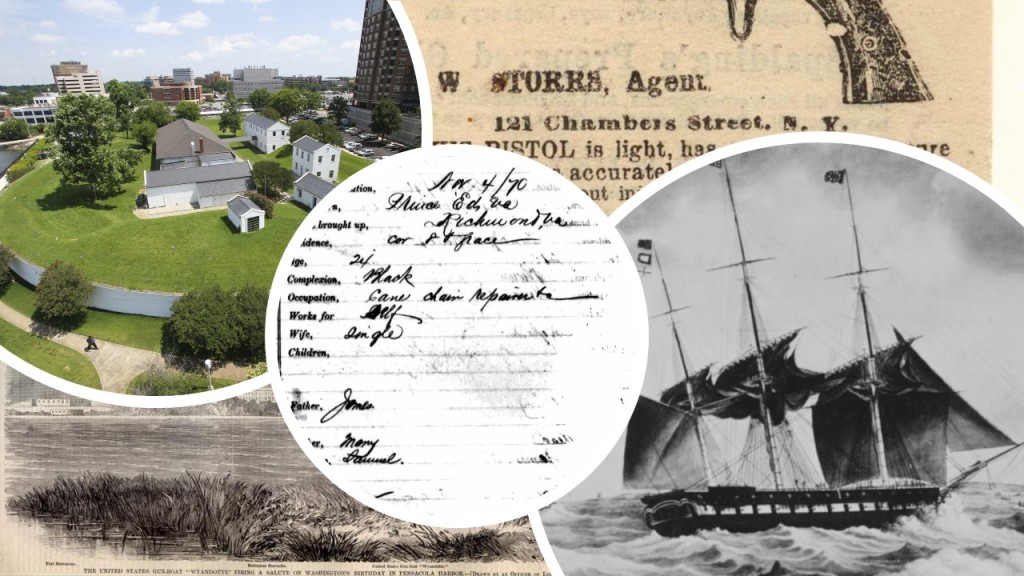

After more than two years service aboard Brandywine, Frank was transferred. He was assigned to another store and guard ship, USS Wyandotte, which was then permanently stationed at Norfolk, Virginia. When he joined her crew in November 1864 Frank was also promoted to the rating of 1st Class Boy. Despite his young age, he seems to have been well respected among the crew, and was evidently well able to meet the physical demands of the role he was being asked to fulfill. A remarkably detailed account Frank recounted in the late 1880s provides us with insight into just what that work could entail. The events he described occurred around the end of 1864, when U.S. preparations for the assault on Fort Fisher, North Carolina were ramping up. Frank and his comrades were being called upon to gather ammunition for the attacking vessels, some of which was being stored onshore at Fort Norfolk. Frank takes up the story.

I was called up at night to take my crew ashore to help load a boat with ammunition. I was then Acting Coxswain of the First Cutter [one of the Wyandotte‘s small boats], I received Boy’s pay but done man’s duty. I took my crew ashore and went to work loading a small hand car used for the purposes of transferring shells from the magazine to the dock. I as Acting Coxswain did not have to work but see it done, but by leaving men at the dock we were a man short and the Master’s Mate whose name I can’t give now told me to lend a hand, so I took the place of the third man on the ground. One man in the locker passing out [a] 100lb shell to another man on the shelf walk and I on the ground with two shell boxes on which I landed the shell then put them on the car. No, I can’t tell who the man in the locker or the man on the walk shelf were, you see I was among a new set of men after my ship burned. Well as the man passed me a shot, the strap by which we handled the shot and shell broke. My right hand was up above my head in the act of receiving the shot from the comrade, my left hand resting on the top and edges of the box. The strap breaking in the comrade’s hand the shot descended upon my hand, catching my hand and crushing it.

Badly injured, Frank was taken from the Fort for medical attention aboard his ship:

I was immediately taken aboard the ship where the Surgeon’s Steward dressed the hand, I can’t name him. The whole top of the hand – the second, third and fourth fingers was crushed and the wrist damaged. The steward dressed the hand splinting it up. I was then sick from the injury and in the sick bay on the Wyandotte a month and a half, then my hand seemed to get better and still carrying it in a sling I tried to do duty, light duty carrying the mail and steering the boat. But my hand would not heal up and kept breaking out and running [weeping, suggesting it was infected] and continued so until I was transferred to the ship North Carolina. While on that ship in Brooklyn Navy Yard I did no duty and was treated by taking medicine for my blood, bathing and caring for my own hand. I can’t tell the surgeon’s name who gave me the medicine but I was very sick from my hand and it running. I was on the ship North Carolina, I was on what they call the Cob Dock a piece of land about two acres which meant the North Carolina would not hold the half of us and we were kept on the Dock, from there I was discharged.

At the time of his discharge Frank was at most 15-years-old. He now had to to fend for himself, in a city with which he was unfamiliar, and with an injury that greatly restricted his employment opportunities.

At discharge I went over to New York City and was [a] stranger and did not know any body and did not know where my father was. I wandered round for a time and done some errands and fell in with Eddie Glasson son of Commander Glasson of Brandywine and he knew about my hand and asked me about it. I finally became sick again my hand running and I lodged with a colored man, a coach man named Charles Riley, he is dead. While there he called in some old doctor who upon examining my hand said he could not cure me as inflammation [sic.] had set in and the poison was all through my system. So he amputated my hand and wrist he said if the wrist had not been broken and the proper care been given I might have had the thumb and fore finger saved but the broken wrist was the cause of the running sore. No sir, I can’t tell who the doctor was I did have his name but lost it when I lost my discharge. In a month or so after the amputation I found my father was in Richmond, Virginia and I went there and stayed a year and a half and was treated by a Dr Brown who said I had blood poison[ing] and some dropsical tendencies but I got well and my arm healed and has been well since. I then came to Springfield, Massachusetts about Spring of 1867, where I lived until about four years ago.

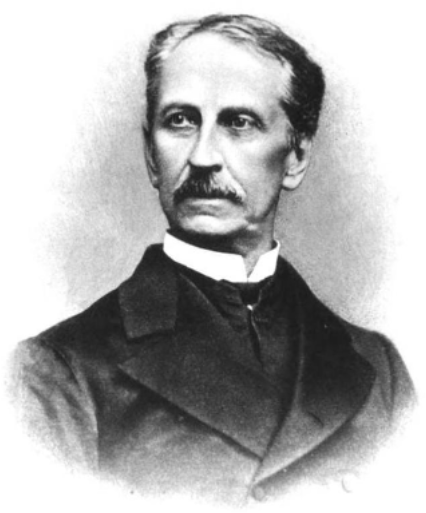

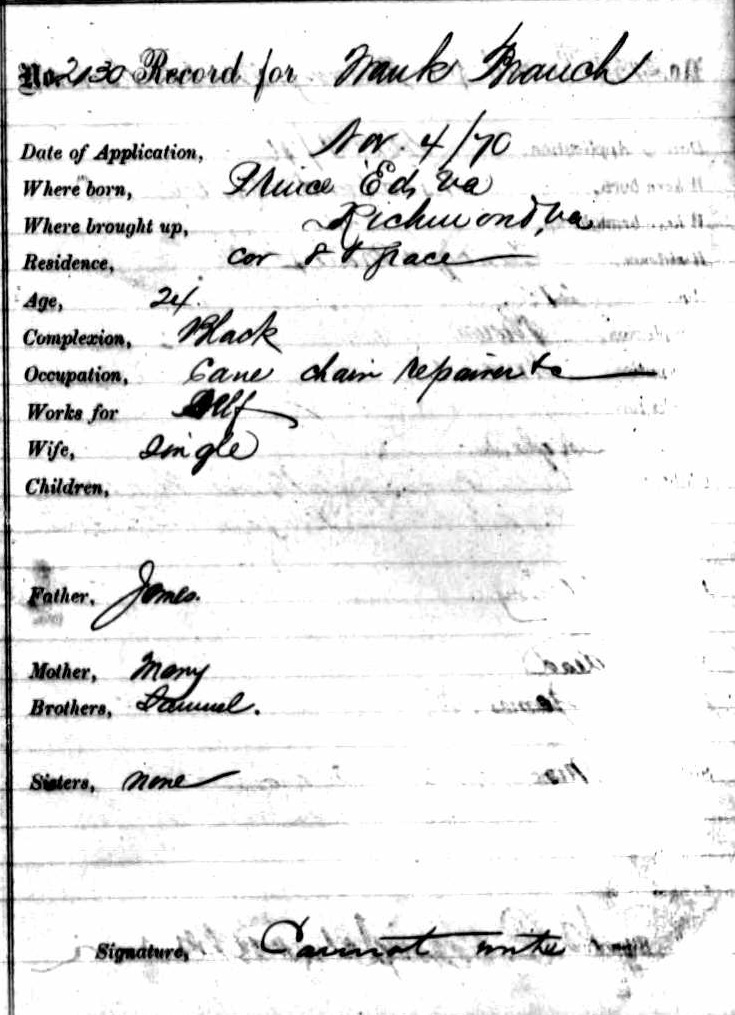

Frank was living in Troy, New York, when he provided this account of his wartime activities to the Pension Bureau in 1888. He was still just 38-years-old. During his dealings with the Bureau Frank also had occasion to shed light on his life in the years before he joined the Navy. He described the momentous decision to emancipate himself and escape enslavement in deceptively simple language. “I did run away from home when I was 12 years old…from Richmond.” Though little more than a child, Frank had successfully escaped enslavement in the Confederate capital to cross beyond Rebel lines and begin a new life as a United States sailor. Although Frank provided no details as to how he made his escape, it may well be that he took advantage of the presence of the U.S. Army of the Potomac, which was located just a few miles outside Richmond in the summer of 1862. What Frank did supply was the name of his former owner. He was the Reverend Moses Drury Hoge, pastor of Richmond’s Second Presbyterian Church. Hoge was a significant figure in wartime Richmond, and a strong supporter of the Confederacy. Many significant figures in both the Confederate administration and military knew him and had attended his church. Yet when Hoge was approached by the Pension Bureau In 1889 to verify his former ownership of Frank, he denied knowledge of him. He was willing to confirm only that he had owned Frank’s father James Branch, who he said “went North directly after the war.” However, the 1860 Slave Schedule seems to tell a different story. One of the two enslaved persons recorded under Hoge’s name on that census was a 10-year-old boy- matching precisely Frank Branch’s age in 1860. Why the pastor later claimed not to have known the boy is unknowable, is it possible that he harboured ill-feeling towards Frank for having emancipated himself all those years before?

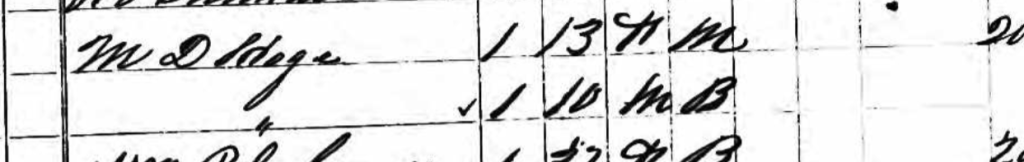

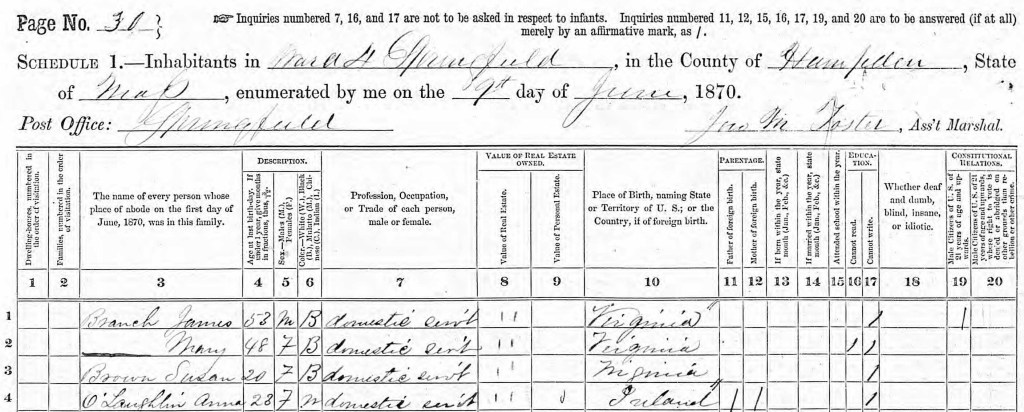

As far as Frank’s post-war life was concerned, the decision of his father James to move to Massachusetts following Emancipation dictated much of Frank’s future movements. The 1870 Census records James and Frank’s step-mother Mary (who had been enslaved to the Dunlop family in Richmond) as domestic servants in Springfield, Massachusetts. Frank had returned to Richmond for a time after the war, and the same census suggests he was still there at this date. But by 1871 he had made what transpired to be a permanent move north, marrying that year in Springfield. His wife Luvenia had also been born in Virginia, and had likely also been enslaved there. Unfortunately, the marriage was destined to end in acrimony, but the couple were still together in 1880, when they were living at Willow Street, Springfield with their children James (5) and Mary (2).

Such is the detail we have detail on Frank’s life during this period that we can even track much of his 1870s employment history. For example, he spent nine months with Henry Hallett, likely working in the pistol shop Hallett kept in Springfield. After that he moved on to the famous Smith & Wesson gun manufacturers, where he spent another five months. A year as a janitor with the School House Department followed, after which Frank was in the employ of merchant William Patton for nine months. Next he worked for a George Brown for two months, then an E.W. Dickinson for 1 month, before finally securing 2 1/2 years employment with a Mr. Wyman, who was most likely a blacksmith. After that he did work looking after the horse of Dr. David Clark. The 1880 census listed Frank (or ‘Franklin’ as it records him- it also adds almost a decade to his real age) noted that he was a “laborer,” but such a simple and deceptively straightforward term belies the reality of his working life over these years, which was marked by a variety, precarity and impermanence of employment that was frequently the reality for poor working-class men. In Frank’s case, the challenges he faced must have been greatly exacerbated by his disability, which was likewise recorded in the 1880 census.

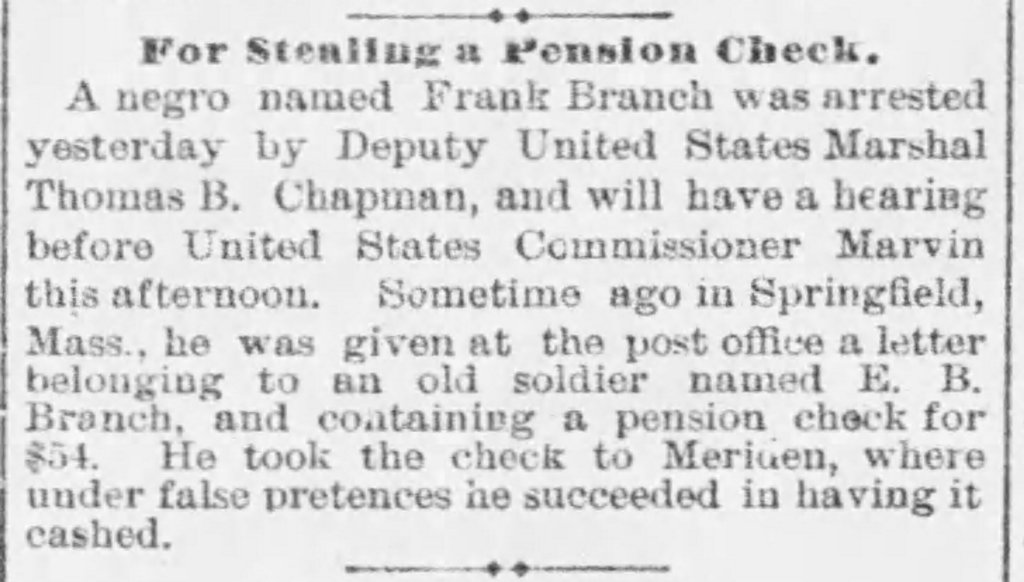

Although his early life had been marked by hardship and struggle, the 1880s were to prove a particularly tough decade for Frank. His marriage to Luvenia ended in 1880, and further stress and worry was coming down the tracks. In 1884 charges were filed against Frank for alleged fraud. He was accused of knowingly impersonated a veteran called Erskine B. Branch and falsely signing his name in order to secure $54 of pension money. The case went all the way to trial, with Frank’s freedom hanging in the balance. However, Frank was unable to read or write, and it seems to have been convincingly argued that he had not knowingly committed the fraud and that his illiteracy had been taken advantage of. A jury found him not guilty of all charges. But despite his proven innocence in the case, the fact that it occurred at all was enough to raise the future suspicions of the Pension Bureau. Within a few short years allegations that Frank’s wartime hand injury may not, after all, have occurred in the naval service began to emerge. With such rumours swirling, the Bureau soon began to investigate. They centred their inquiries centred around both the cause of Frank’s injury, and his movements in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War.

Much of the evidence left to us in Frank’s enormous pension file was created in response to the Pension Bureau investigation of the late 1880s. It was sparked by allegations that Frank had not spent a long time in Richmond after the war as he had claimed, but had actually gone off and joined the navy in Cuba. It was while there, so the story went, that his hand was struck by a cannon shot fired during an altercation with “natives of a West Indies island.” This version of events was one Frank had allegedly given to his former employer, Dr. David Clark, among others. As a result of the conflicting statements, a series of interviews were conducted with people close to Frank. Many of them contradicted each other, with some supporting Frank, some casting doubt on him. As was often the case when white men were supplying evidence in an African American Civil War pension case, prejudice and racism were never far from the surface. One example came in Dr. Clark’s description of his former employee, whom he characterised as “a sober man but somewhat lazy as most of the colored people are.” It is difficult at this remove of time to determine the real truth. There was no doubt Frank had been injured as he had described during the Civil War, as it was corroborated by former comrades, although some (white) sailors questioned the longevity and severity of his injury. However, it seems somewhat improbable that he immediately left New York to head for Cuba and a battlefield wound, in an unnamed engagement, that just happened to strike the very same hand damaged at Fort Norfolk. Frank apparently did tell some people this “Cuba Cannonball” tale, but it may simply have been the concoction of a young man trying to add mystery and excitement to explain a disabling wartime wound that had been inflicted in such mundane circumstances. In addition, some of the confused testimony Frank provided with respect to time and place was likely a consequence not of duplicity, but the fact he was unable to read or write. Illiterate people often marked time in different ways, and frequently struggled with providing information surrounding precise ages and time periods, particularly after the passage of years. An example of this can be seen in one of Frank’s responses when asked how long he had stayed in Richmond after the war. He responded not with a timeframe, but the fact it was “long enough to vote two or three times” (as an aside, this shows how momentous and memorable an event in his life it was to be able to cast a vote as a free man).

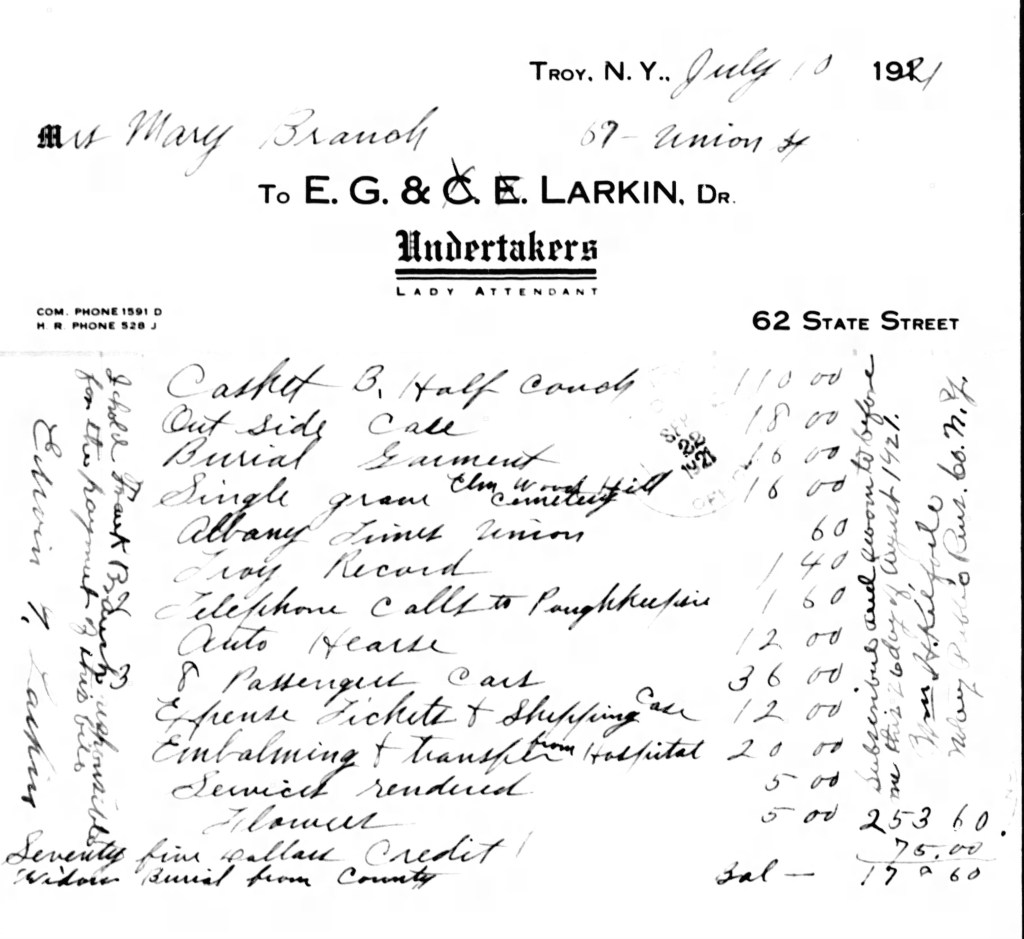

Frank’s quest for a Civil War pension may have been blighted by questions over his integrity, but in the end his wartime service did provide significant benefits to his new family. He had married again in the 1880s, tying the knot with Mary Phillips. She was a few years younger than Frank, having been born around 1868. They settled down in Troy, New York where they raised a number of children, Frank Jr. (b. 1888), George (b.1891), and Alice (b.1894). By the time Frank was recorded on the 1891 Veteran’s Schedule in Troy, he was still proudly referencing his wartime role as Acting Coxswain. The former child sailor was still a relatively young man when he passed away on 26 September 1898. He was buried in Troy’s Oakwood Cemetery. His widowed wife Mary successfully claimed for a widow’s pension, which she received until her own death in 1921. The bill for her funeral (below), listing the different services provided by the undertakers, was reimbursed to the family by the U.S. Government. It was a fitting close to a pension claim that had caused Frank such heartache while seeking to prove his entitlement to it, all those years before.

The remarkable story of Frank Branch is just one among thousands accessible to us as a result of the extensive naval documentation that survives relating to U.S. sailors of the American Civil War. Such is their detail that we can often look beyond the names and descriptions on muster rolls of vessels like USS Brandywine and USS Wyandotte to reveal new information about the wartime, pre-war and post-war lives of these men and their families. As Frank’s story demonstrates, these records are especially invaluable with respect to African American service, many of whom had previously been denied even their own names in the historical record. It is only through the work of volunteer citizen scientists such as those from the African American Historical & Genealogical Society that we can recover these stories.

If you are interested in participating in the Civil War Bluejackets Project, you can head over to our Zooniverse Project Page to take part. And remember, we are always interesting in hearing what our community uncovers, so please let us know on Zooniverse Talk what you come across- we are certainly delighted that @Grobster chose to do so when it came to Frank!

2 responses to “Bluejacket Community Discoveries: On the Trail of an African American Child in the Union Navy”

[…] the post-war United States (You can read about this research into Frank Branch on our website here https://civilwarbluejackets.com/2023/09/20/bluejacket-community-discoveries-on-the-trail-of-an-afric… and here […]

LikeLike

[…] You can read about this research into Frank Branch on our website here https://civilwarbluejackets.com/2023/09/20/bluejacket-community-discoveries-on-the-trail-of-an-afric… and here […]

LikeLike