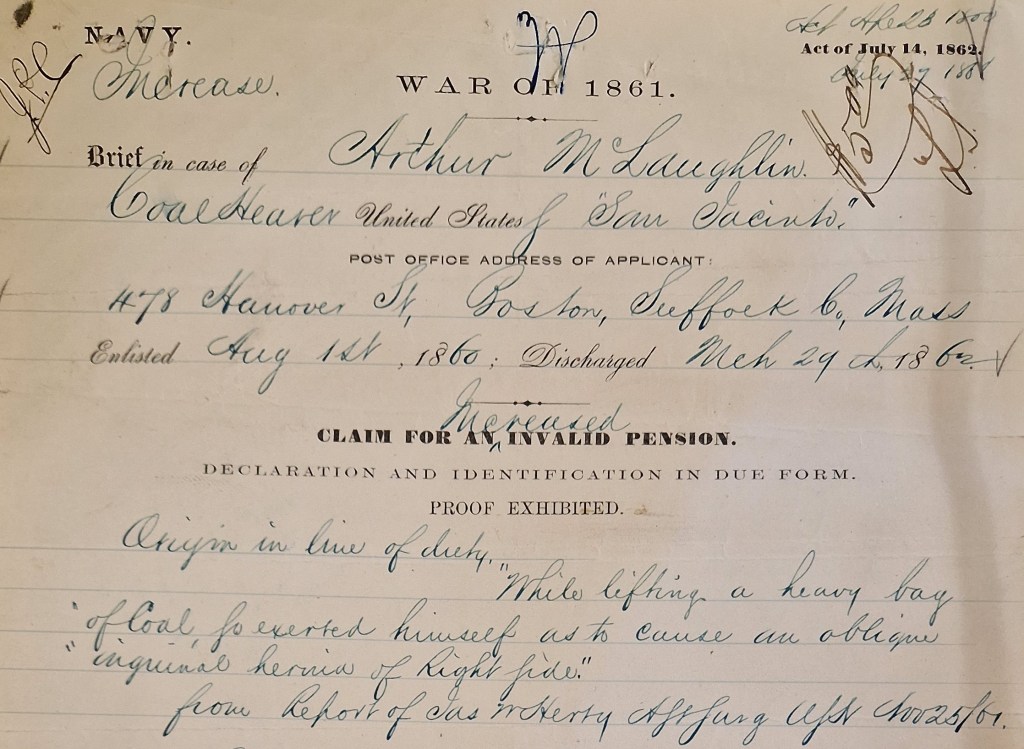

Anyone who works with Civil War pensions—particularly those of naval veterans—will have encountered men who suffered from hernias. In their applications, they usually blame lifting heavy materials or being struck by an object (but for more on that, read on). Though easily treated today, hernias were extremely debilitating in the 19th century, causing both severe pain and threatening laboring men’s ability to earn a living. In this special post, Civil War Bluejacket’s Zooniverse Moderator (and retired physician) Robert Croke explores just what hernias were, and what they could mean for those who suffered from them.

Hernia was among the most common medical problems Civil War veterans cited in requesting a pension from the Federal government. In medicine the word hernia or rupture refers to the protrusion of an organ normally contained in one body cavity through the wall of that cavity to an adjacent space, and they can occur in many places in the body. In the everyday language of pension applications, it almost always referred to a groin hernia.

The groin is a weak spot in the wall of the abdominal cavity because it has an opening for a vein, artery and nerve to pass between the abdomen and leg. Our upright posture means that gravity presses the small intestine against that opening. A defective fibrous membrane responsible for containing the intestine while allowing free passage for the normal parts can allow a loop of intestine to exit the abdomen. The compartment into which it escapes is very confined, so it makes a lump visible and palpable in the skin.

Most of the time the patient senses the situation and can manipulate the lump to move the intestine back where it belongs, ie, the patient reduces the hernia without external help. However, if this is unsuccessful and the fibrous membrane squeezes the intestine, its blood supply and return are impeded. This results in swelling, further interfering with reduction of the hernia, and causes death of that loop of intestine. This situation is called strangulation and is immediately life-threatening.

The odds of suffering strangulation are very low (three of 880 subjects over one to two years) but the consequences are very serious. Without surgery it’s fatal. Even in the modern era the risk of death during surgery in that circumstance is markedly elevated over that of an elective procedure. Further, follow-up studies show that a large fraction of people with reducible hernia eventually seek surgical repair because of pain. Current guidelines therefore call for having a low threshold for elective surgery, which is now done with near-zero risk of death or permanent disability.

The 19th century was different, however. Pasteur did not publish his revelations regarding germs until 1864 and it took until 1880-1900 for the discipline of microbiology to be securely laid. Joseph Lister applied Pasteur’s principles in the operating room early but the chemicals available for the purpose were toxic. Decades elapsed before the problems were worked out and asepsis became the standard. Until then any operation was likely to be complicated by severe infection.

In addition, for groin hernia, surgeons tried unsuccessfully many techniques until in 1891 an operation was devised—simultaneously by an Italian and an American surgeon—that proved durably effective.

Therefore it was the beginning of the 20th century before a safe cure for a groin hernia became available. Until then patients used various garments and appliances, collectively called trusses, to apply pressure to the skin and keep the intestine from escaping the abdomen. They didn’t work. People lived with the discomfort and pain and with the constant worry of potential strangulation followed by death.

A late 20th century estimate of the lifetime risk of developing a groin hernia is 27% for men and 3% for women. Statistics for earlier times are not available, but we don’t have reason to think the risk was different during and following the Civil War.

Strong causes and risk factors of groin hernias are male sex, increasing age and family history of the same problem. The literature cites a variety of other factors with weaker association. Counter to intuition and popular belief, heavy lifting is not the root cause, rather the tissue defect is. Of interest, weight-lifting athletes have the same risk of hernia as the general population. However, it is during a lift that the tissue bulges through the defect, causing pain. Therefore, the sufferer is disabled, sometimes severely as in the case of Johann Jacob Bubec in the illustration above.

With our 21st century information, we can now summarise in greater detail than was possible in the 19th century some of the key facts about hernias:

- About one quarter of men develop a groin hernia over their lifetime.

- It is not an occupational hazard, rather a consequence of being male, getting old and being in an unlucky family.

- It is uncomfortable, painful and disabling, with a low but cumulative risk of death.

- It is safely curable since about 1900. Until then people lived with the discomfort, pain and risk.

Sources

- Triumphs and Wonders of the 19th Century: The True Mirror of a Phenomenal Era, James P. Boyd. Original Copyright 1899. Gutenberg eBook #55390

- Groin Hernias in Adults, Robert J. Fitzgibbons, Jr., M.D., and R. Armour Forse, M.D., Ph.D. N Engl J Med 2015;372:756-63

- History of Surgery, Brittannica

- Joseph Lister (1827-1912): A Pioneer of Antiseptic Surgery, Cureus