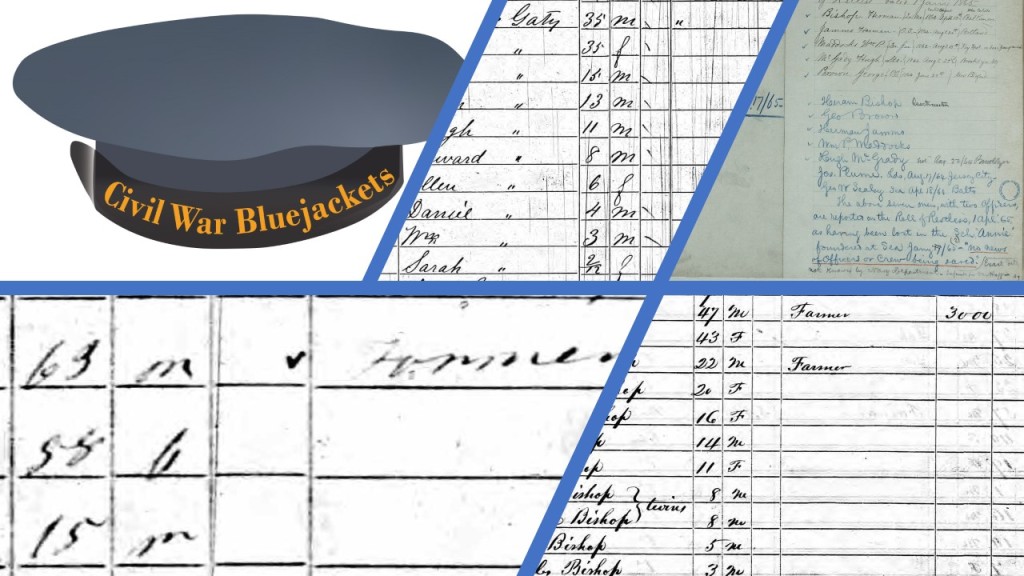

For our latest Bluejacket Community Discoveries post, we take a look at the only muster sheet that relates to the unfortunate U.S. schooner Annie. The sheet has been worked and commented on by a number of our Civil War Bluejackets Community, including @mermex, @Beth52 and @KaiserSnowse. The reason it has drawn particular attention is its unusual form. It consists only of a short list of names, with the additional detail that the Annie served as tender to USS Restless, and that the seven men recorded (with two officers) were “reported on the Roll of Restless…as having been lost in the Sch[ooner] Annie foundered at sea Jany 17 ’65 – no news of officers or crew being saved.” To learn more, we decided to take a look at the Annie, what are known of her final moments, and see what might be discovered about the listed men who perished aboard.

The Annie was a small schooner that had been captured by the USS Fort Henry in the Suwanee River on 26 February 1863. Placed in Federal service later that year, she became a tender serving the East Gulf Blockading Squadron off the Florida coast. By the beginning of 1865 Annie was specifically servicing the needs of USS Restless, a bark crewed by 66 men. Restless was a particularly successful blockader, having taken numerous Confederate prizes. USS Annie‘s tiny crew on her final voyage were drawn from among the men of the Restless. That voyage began on 30 December 1864, when Annie left Key West with orders to proceed to Charlotte Harbor on Florida’s west coast and commence blockading duties- neither she, nor her crew, were ever heard from again.

As January 1865 progressed and no word was heard of the Annie, concerns began to grow as to her fate. Towards the end of the month those fears were further stoked when the wreck of a schooner was sighted off the Florida coast:

“…about 12 miles to the northward of Cape Roman he [another schooner captain] passed the wreck of a schooner with her mainmast and foremast broken, and that night he saw a large fire ashore”

Following the report, a search for the Annie and her crew was quickly instigated. In early February the USS Hendrick Hudson arrived at the supposed wreck site; her commander Acting Volunteer Lieutenant C.H. Rockwell gave the following account of what they encountered:

On the 5th I again weighted anchor, and, with a smooth sea and very favorable circumstances, succeeded at 1 p.m. in discovering the mast referred to in 6 fathoms of water, Cape Roman bearing N.E. by N., distant about 10 miles. I immediately hauled the bow of this ship alongside the mast, and with such means as I possessed succeeded at 11 p.m. in raising the wreck sufficiently to bring her bow out of the water and identify her as the Annie, and discovered her condition. The catastrophe by which she was wrecked is still a mystery, and unless her crew have been saved I fear must remain so. From her foremast aft her deck is entirely gone, with the exception of the port side of the trunk cabin aft. From just abaft the fore rigging, on the starboard side, she is entirely gone- deck, bottom, timbers, and everything from the keel out being completely cut off, with the exception of two or three of her floor timbers. No vestige of her mainmast or the sail could be discovered, not even the stamp. The pole of the maintopmast was found fast to the jib stay, the pennant halyards being wound around it with the toggle head of the pennant. On the port side, from the fore rigging aft, her rail was entirely gone, but I think her plank-sheer was whole on that side as far as the cabin. A more complete wreck could scarcely be imagined…From all I could see I think she must have been blown up, and can account for it in no other way.”

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Volume 17

No trace of the Annie‘s crew was ever found, all seemingly having perished in the huge explosion that rocked the ship. The reconstructed muster that our community members have worked on was an attempt to record the men who had been aboard (the two officers being listed separately). As well as being an example of how the Navy sought to record lost crew, this sheet also demonstrates that mistakes could be made- analysis of the muster roll of the USS Restless used to create indicates that one of the lost sailors has been omitted from this list- Ordinary Seaman Frederick Nelson. Using the Restless muster, we have recreated the basic details of the unfortunate crewmen in the table below. Their service history shows that they were drawn from a range of nationalities and had a mix of naval experience, from seasoned mariners to recent recruits.

| NAME & RATING | AGE | LAST ENLISTMENT PLACE & DATE | NATIVITY | OCCUPATION |

| Quartermaster Hiram Bishop | 35 | Baltimore, Maryland 18 April 1864 | Burlington, Vermont | Mariner |

| Ordinary Seaman George Brown | 24 | New Bedford, Massachusetts 28 June 1864 | Scotland | Machinist |

| Ordinary Seaman Herman Jamma/Jamme | 25 | Portland, Maine 24 August 1864 | England | Soldier |

| Quarter Gunner William P. Maddocks | 19 | Key West, Florida 15 August 1862 | Maine | None recorded |

| Landsman Hugh McGady | 20 | Brooklyn, New York 22 August 1864 | Ireland | Laborer |

| Ordinary Seaman Frederick Nelson | 22 | Baltimore, Maryland 18 April 1864 | Spain | Mariner |

| Landsman Joseph Plume | 20? | New York, New York, 17 August 1864 | New Jersey/Ireland | Laborer |

| Seaman George W. Sealey | 23 | Baltimore, Maryland 18 April 1864 | Maryland | None recorded |

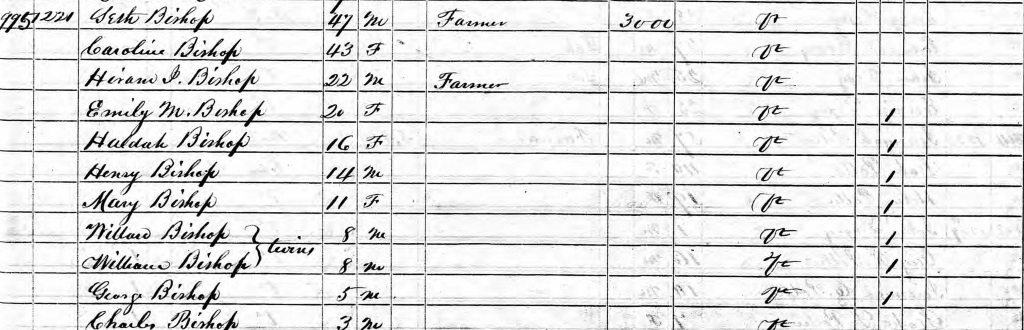

The pension files associated with some of these men allow us further insight into their lives. Take for example Quartermaster Hiram Bishop, who had originally come from a farming background in Burlington before choosing a life at sea, probably some time in the 1850s. His death widowed his wife Sarah, and left fatherless his daughter Carrie Jane, who had just turned 11 when Annie exploded, and son Elmer Hiram, who was just 4-years-old.

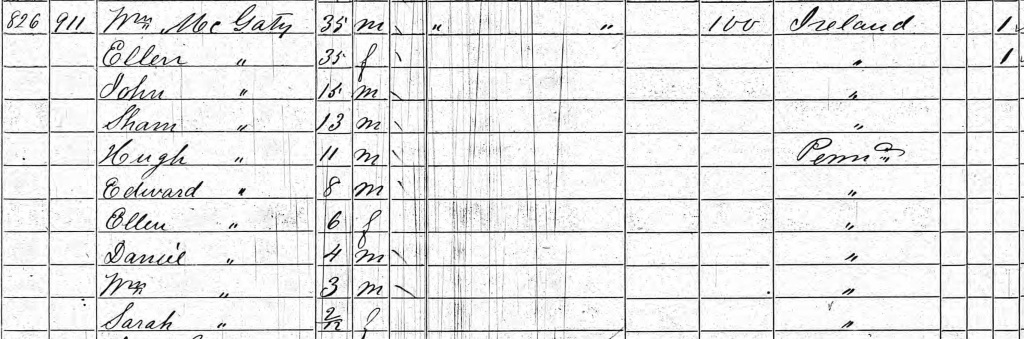

Another of the bereaved families we encounter are the Irish McGadys. Although Hugh McGady enlisted in New York, his family made their home in Allentown, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, where they were recorded as “McGaty” on the 1860 census. Interestingly, although Hugh was listed as of Irish nativity in the navy, he was recorded as the first of the family to have been born in Pennsylvania on the census. The nativity locations of the McGady children on that census also reveal that the family were Famine emigrants, having departed Ireland in the late 1840s. Hugh’s file also contains his precise date of birth, given as 24 September 1848, indicating that he lied when he enlisted, and was just 16-years-old when he died.

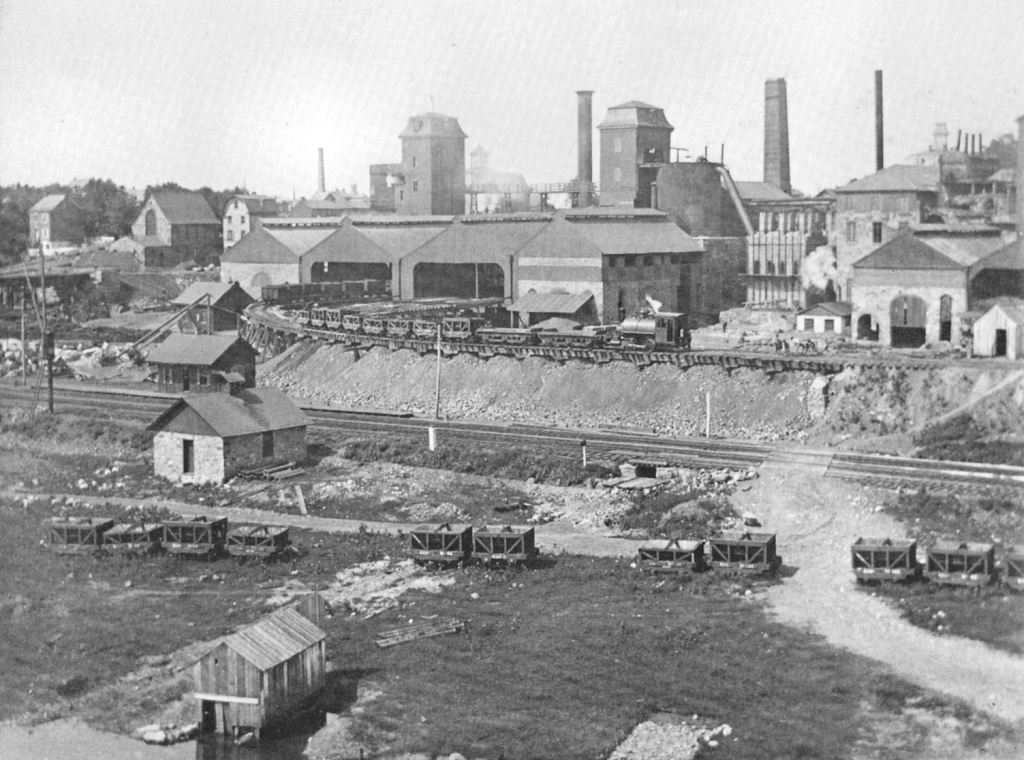

Hugh McGady’s decision to enlist in the naval service may have been influenced by his father William’s reduced capacity to support the family. A laborer working on one of the Allentown Iron Company’s blast furnaces, his health was apparently beginning to fail by 1863. In such circumstances, Hugh’s naval income would have been a welcome addition to the family’s income sources.

Although we can’t be certain where in Ireland the McGadys were from, their surname and the names of those Irish neighbors who provided statements for them (such as the O’Donnells and McFaddens) indicate that it was certainly Ulster, with a very strongly likelihood they originated Co. Donegal. One such statement, given in Allentown by a Hugh McGeever, also provides a rare mention in Civil War era records of the Irish Famine. It also demonstrates that those from the same locality in Ireland often also made their homes close to one another in America. In his statement, McGeever recalled that he had “intimately known William McGady and his family almost from the time they learned to known anybody…[the McGadys were married] in the year 1844…they well remember that it was a few years before the great famine in Ireland- the famine of 1846 and 1847…”

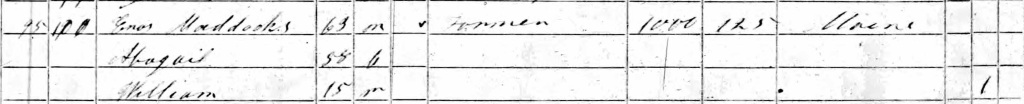

The final Annie crewman we took a look at was young William Maddocks from Maine. Although it is not stated, we know that William had been in the U.S. Navy for more than two years at the time of his death. Similarly, although his naval records list no occupation, his pension file indicates that prior to enlistment he was working out as a farm-laborer near the town of Washington, Knox County, Maine. William was the son of Enos and Abigail Maddocks and was by far the baby of his family- he was almost 10 years younger than any of his siblings. Though his father ran a farm in Washington, sailing was clearly in the blood- in 1850 two of the older Maddocks children were recorded as seamen. But by 1860, only William was left at home, where he was helping with the support of his ageing parents. The role he had taken on is made clear by the extremely poignant piece of evidence they submitted in their pension claim- the last letter they ever received from their son:

U.S. Sloop Rosalie August 14 1864

Dear Mother

I received your kind letter on the 12th of this month and was very glad to hear from you again. I was glad to see Martha’s [William’s sister] picture. I am two years shipped today so I have one more to stop. I expect that by [the] time this will have reached you something will have turned up. I expect times is very hard there now but try and hold out till I get home for I shall save all the money I can for it takes a good part of my wages to keep me in clothes they are so dear. When you write please to let me know how you stand and then I will know what to do. The Yellow Fever is dreadful in this squadron, the Bark Roebuck had only 5 men left out of 60 her regular crew. I cannot think of any more to write at present. Give my love to Father and Martha and all enquiring friends.

So Goodbye,

From your affectionate son,

Wm. P. Maddocks

U.S. Sloop Rosalie, East Gulf Squadron, Key West, Fla.

Despite it’s brevity, the reconstructed muster list of men who lost their lives aboard USS Annie in January 1865 offers us remarkable insights into the backgrounds of some of the men who donned the Union Bluejacket during the American Civil War. Many thanks to @mermex, @Beth52 and @KaiserSnowse for highlighting it. If you would like to join them in shedding new light on these and other sailors, we are always keen to welcome new members to our transcribing community- just come on over to our Civil War Bluejackets Zooniverse Page to get started!

One response to “Bluejacket Community Discoveries: Recovering the Last, Lost Crew of USS Annie”

[…] about four-in-ten navy men were foreign born, but the variety is spectacular. The same site has a list of men lost when the small Union schooner Annie went down in […]

LikeLike